Daniel Cross

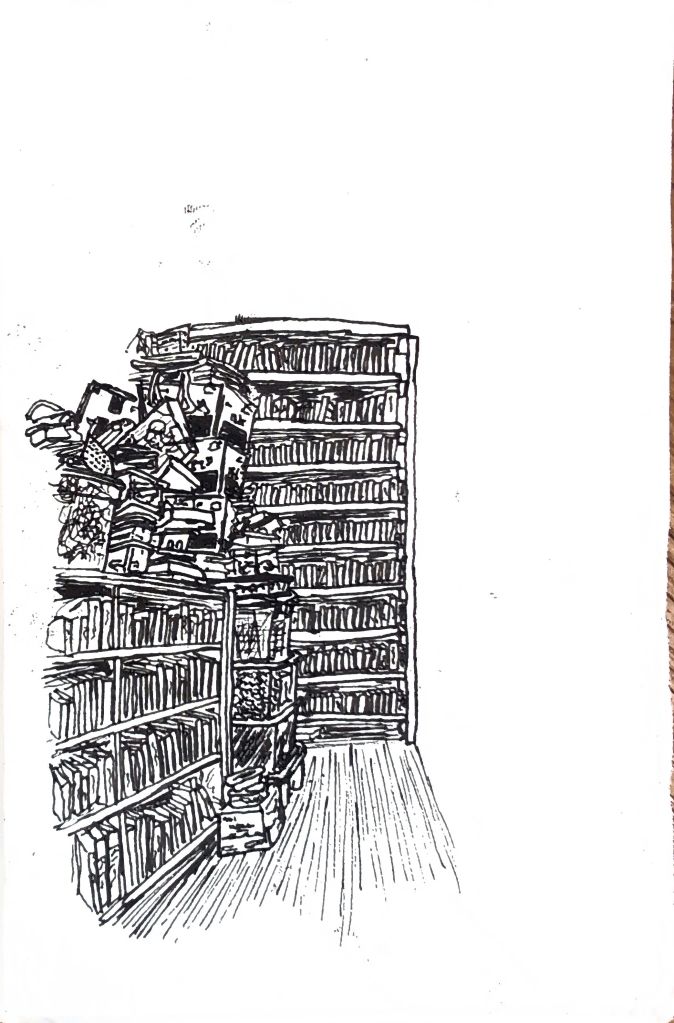

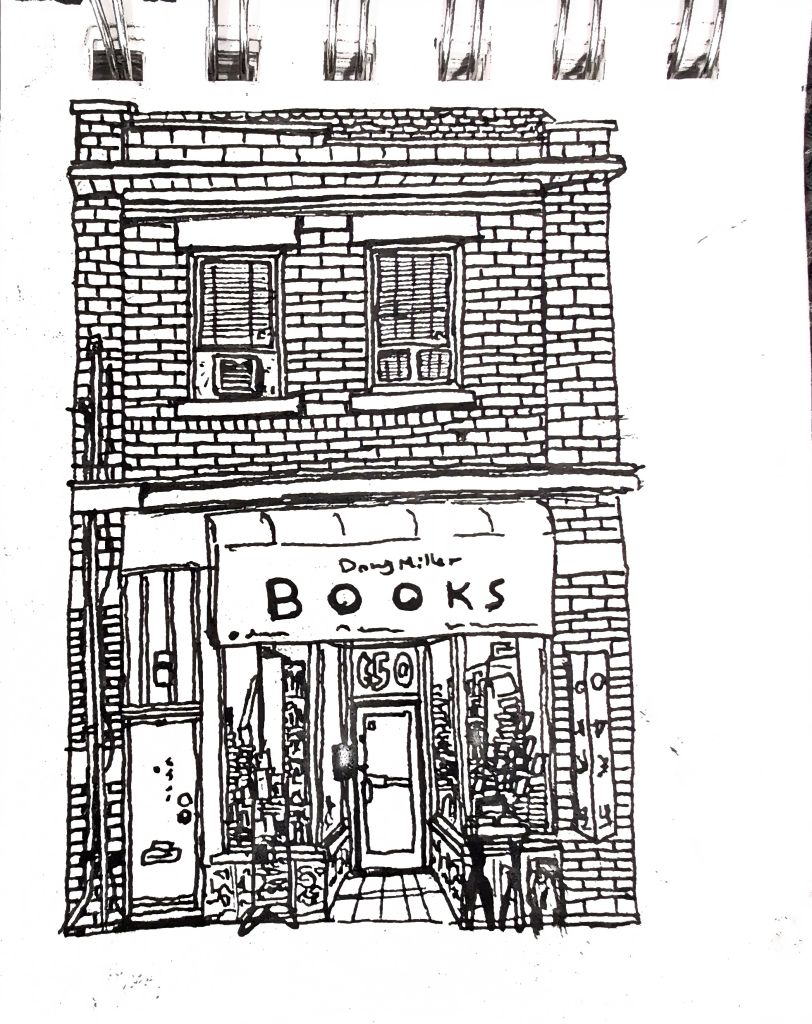

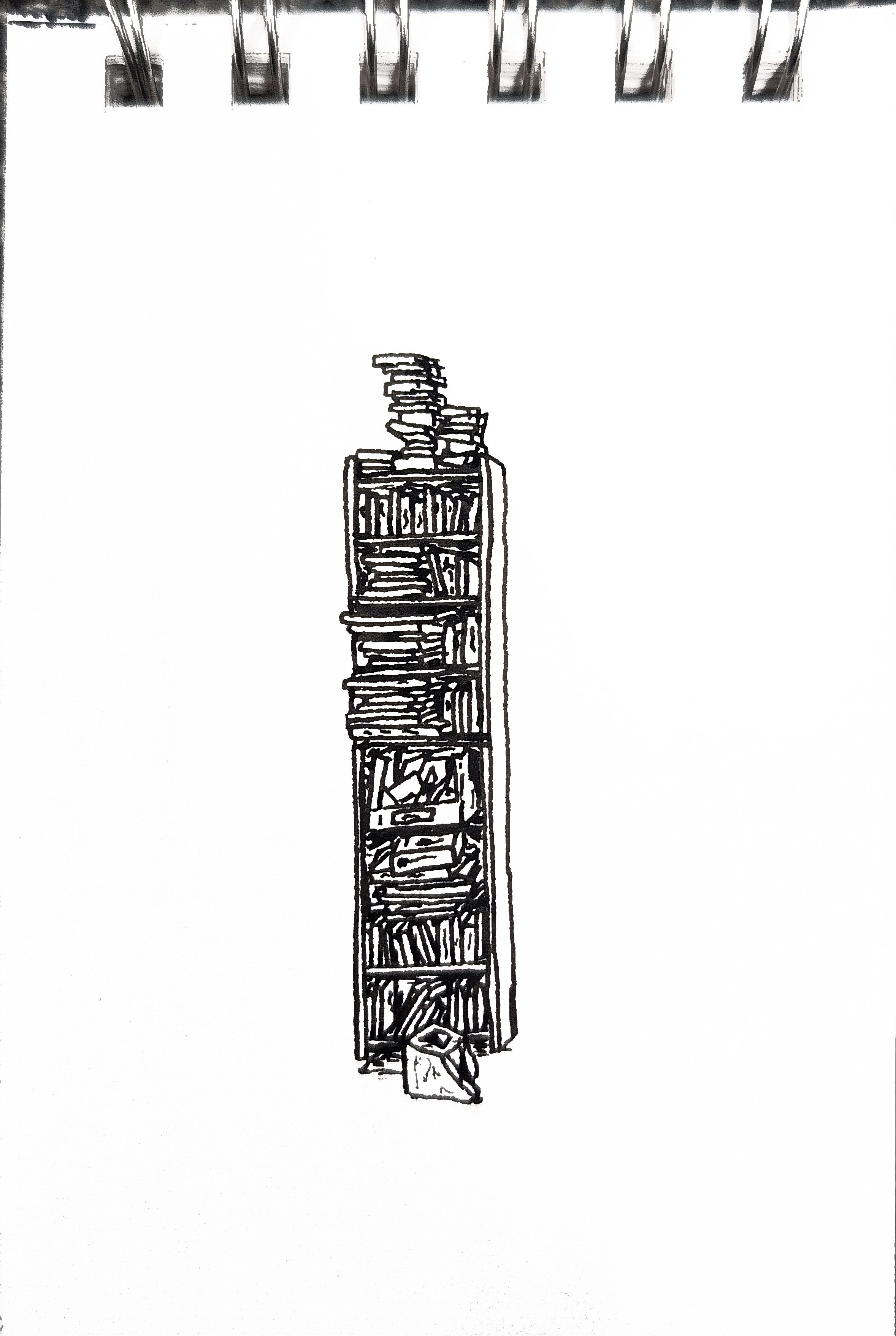

As you enter the bookstore, the sounds of the Bloor Street traffic fade away, replaced by the thick quiet of soft creaking footsteps and rustling pages. Its small interior is made even smaller by the stacks of books and boxes sitting in front of the huge shelves, leaving just enough space in the aisles for a single person to walk through or two people to carefully squeeze past each other. The shelves are divided into sections, some labelled with categories like “LITERATURE/FICTION,” “History, Biography, Politics etc…” and “$3 Specials (and up).” Other sections are unlabelled; some still easily identifiable, like the sci-fi/fantasy section right at the back, some less obvious. The long and narrow room stretches away from the front door, and as you move deeper inside, the clutter becomes even more present and the aisles are slightly darker and more cramped. The smell of books, bibliosima, is at its most intense near the back; it is a deep, comforting smell, slightly woody.

Sometimes classic rock or jazz plays quietly from a small speaker on a desk about halfway down the length of the store. The surface of this desk, which serves as the checkout, is completely covered up by piles of books which can obscure whoever is sitting behind it. Usually this is Doug, the owner and namesake of the store, though he can also regularly be found deeper into the corridors in front of a wall of stacked bins, sorting Lego bricks by colour or shape. Often it is only him in the store, but at times there are also others helping out, like Bob, who sometimes sits at the checkout, and various young people who help sort books or Lego. Customers come and go, sometimes staying for a while to browse in-depth, sometimes just popping in. Often there are very few of them inside, but at other times the store feels full and bustling; it doesn’t take very many people for the small space to feel busy.

[…]

Relationful Spaces

I came to the idea of Doug Miller Books being relationful in trying to identify the opposite of alienation. I am thinking of alienation in roughly the way that Anna Tsing talks about it in her book, The Mushroom at the End of the World, as the way that “things become stand-alone objects, to be used or exchanged; they bear no relation to the personal networks in which they are made and deployed.” Through her ethnography centered around Matsutake mushrooms, she explores this concept in various contexts and specific applications, and her book is the foundation of my understanding of the idea. To put it another way, alienation is the way that relationships become severed, histories are erased.

On the other side of alienation, we find contamination. As Tsing beautifully puts it, “we are contaminated by our encounters; they change who we are as we make way for others.” Contamination is a wonderful, messy thing; it is the way that we are caught up in relationships. And vitally, “Everyone carries a history of contamination; purity is not an option.”

When I say Doug Miller Books is relationful, I am not getting at the precise opposite of alienation, but something less exact, a vibe more than anything. The idea of a space being relationful gets at the feeling of a place where contamination is rampant. It is something opposed to alienation, sterility, purity. It is the outcome of thorough, ongoing contamination, of being unavoidably caught up in a tangled web of relationships.

Tsing, Anna. The Mushroom at the End of the World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015. References on page 27.