By Hanisha Mistry

Learning Strategist’s days cannot accommodate all of U of T St. George.

The University of Toronto’s St. George campus serves approximately 68,454 students, while the Centre for Learning Strategy Support (CLSS) operates with only 22 professional staff and 12 peer mentors. This stark disparity reflects a systemic imbalance between the student population and the organizational capacity of the CLSS. The limited number of staff underscores a resource constraint that directly impacts the quality and accessibility of support services for students.

This imbalance is felt within the Central Administrative Team at CLSS, where Learning Strategists grapple with the dual pressures of heightened demand and insufficient resources. Administrative meetings capture the essence of this challenge: An ongoing stream of voices fills the hour as team members race to summarize their week’s work. Meanwhile, the Teams Call chat buzzes with side conversations and real-time input, all in an effort to maximize the limited discussion time. Yet, even with these efforts, meetings often run overtime, a testament to the overwhelming volume of work.

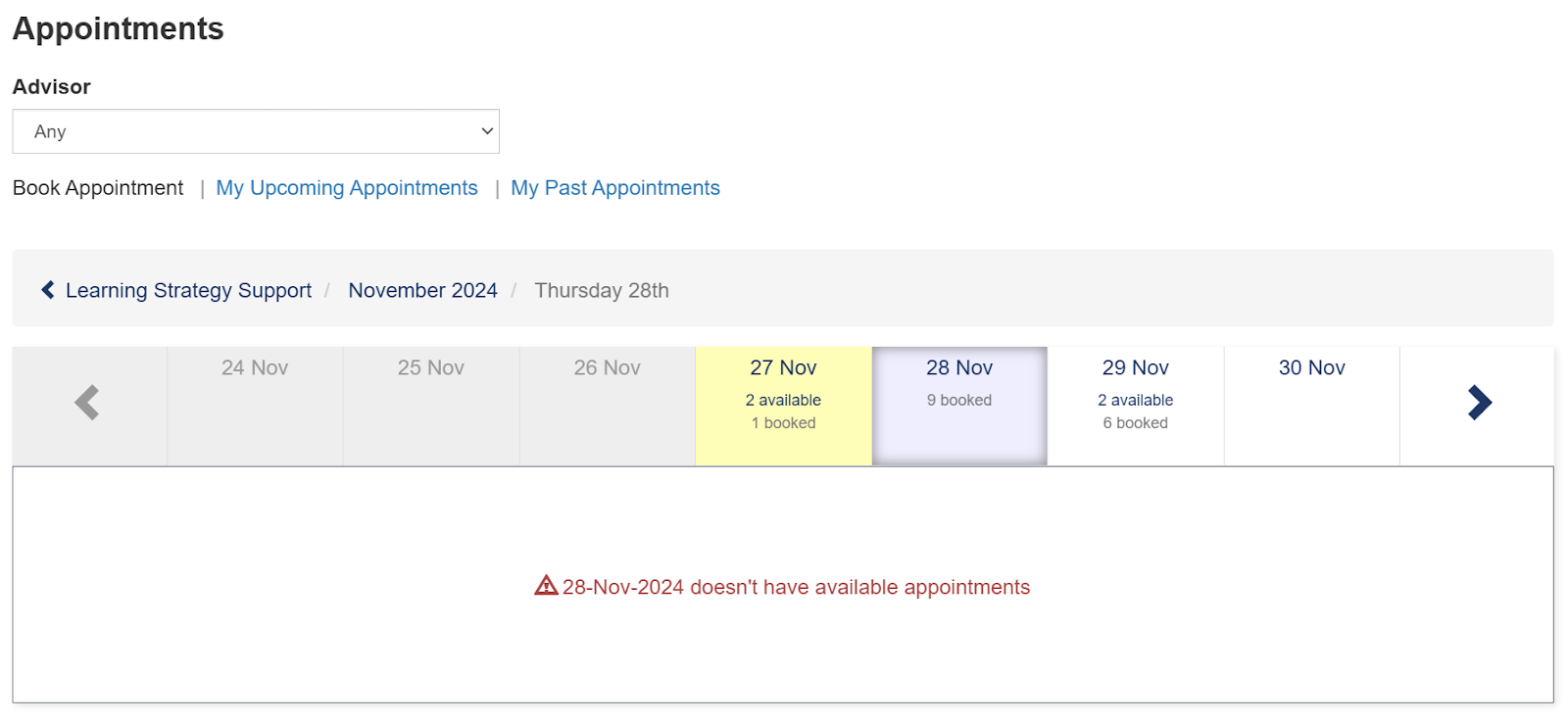

A key example of this strain is the scheduling of student appointments. Learning Strategists report that their sessions are often fully booked within days of opening the two-week scheduling window, leaving students waiting up to 10 days for support. This high demand shows the critical role of Learning Strategists in addressing academic concerns, yet it also strains their limited capacity. Beyond appointments, strategists juggle additional responsibilities, including workshop development, faculty partnerships, and administrative initiatives to address broader student needs. These multifaceted roles intensify their workload, creating a cycle of overextension.

Despite these challenges, the team remains committed to serving the students at the St. George campus. To balance their internal and external responsibilities, they have streamlined internal processes, such as shortening or sometimes canceling meetings, to free up more time for student appointments. The CLSS is also actively seeking to expand its team, recognizing that sustainable and long-term support requires more hands on deck.

The overwhelmed state of the Learning Strategists serves as a dual indicator: it highlights the essential demand for their services while exposing the fragility of an under-resourced system. Their fatigue and exasperation during meetings—reflected in sighs, hurried exchanges, and unspoken uptight tension—are not just personal struggles but symptoms of a larger structural issue. Although students’ consistent engagement with the CLSS demonstrates the critical value of these services, the staff’s limited capacity poses a risk to both service quality and their own well-being.

Without institutional recognition of this imbalance, the CLSS risks burnout among its team and diminished accessibility for students. Proactive measures like team expansion and more appointments are vital but temporary solutions. A long-term commitment to scaling resources in proportion to student demand is essential. By raising awareness of the pressures faced by the CLSS, the university community can advocate for meaningful change. Such efforts—whether through presenting data on unmet student needs, sharing testimonials, or writing a blog post like this—can continue the conversation so that, hopefully the CLSS receives the resources it needs to thrive. Addressing this imbalance is not just about relieving the burden on staff; it is about ensuring the continued delivery of high-quality support for the students who depend on it.