By Molly McGouran and Lukey Lu

From our first meetings with Student Life administration, it was clear that our participant observation would be different from what we expected. Most of the staff work from home; therefore, much of the programming offered by the Centre for Learning Strategy Support (CLSS), where we conducted our work, was offered through Microsoft Teams. The moments for thick ethnographic description, we feared, were going to be hard to come by. However, through the two CLSS administration meetings we were able to attend, we realized that while online ethnography was different from in-person, participant observation, it could still provide us with rich ethnographic data if we learned how to recognize it.

We identified an unforeseen “fieldsite” in the Teams chat and reaction features which offered virtual additions to CLSS administrative meetings. The use of reactions, such as hearts or hands-clapping, liberally accompanied the meetings. We took note of the use of gifs in the chat box, an enhanced visual language. We did not have to infer the emotions and sentiments of meeting participants based only on body language and facial expressions, they were magnified and materialized on our screens.

Besides Teams, a digital space offers ethnographers a different way to connect with the site. ‘Normally,’ ethnographers are physically connected with their participants — we meet, and then we talk. However, in an online space, modes of connection change: every ‘talk’ needs to be

‘booked’ through email beforehand. Email becomes the medium to materialize the connection as every sentence in a message becomes a condensed, visible and traceable exchange between the researcher and interlocutors. This may seem to position the research into an ethnographically ‘limited’ position — we can no longer spontaneously ‘sense’ our interlocutors. Rather, all the information we have about them is mediated through a certain platform — Microsoft Outlook in our case.

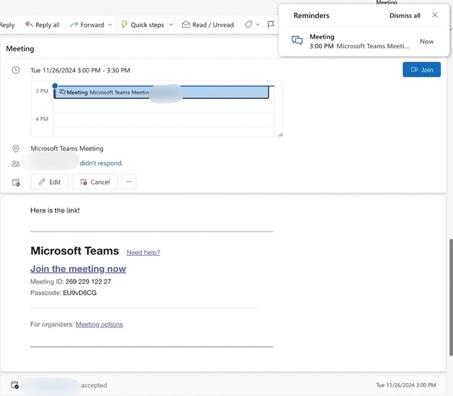

Nevertheless, the medium itself is the language. We lose our direct sensual ‘detection’ of our informants, but we gain a new and irreplaceable way to understand them. In our case, their skillfulness in organically using Microsoft Office entails ethnographic richness: they use dynamic calendars that can easily tell others their status (free or busy, fig.3) by clicking their avatar, they embed Teams (for virtual meetings) links in appointment emails that can automatically add the schedule to attendees’ calendars (fig.4), and they digitize all their archives and organize them through SharePoint. Upon knowing/‘observing’ individual staff from their linguistic expression through email, all of this contextual information enables the ethnographer to ‘unlock’ in a more direct way the social environment and discursive space our SL interlocutors inhabit: one that is highly productive, effective, and self-organized.

Thus, online ethnography seems to entail many obstacles that prevent ethnographers from gaining ‘rich’ data but it also offers us irreplaceable modes to know our participants and their spaces. Virtual events are playing a dominant role in our contemporary life as a ‘new way’ of living. The same should apply to ethnography — ethnographers should also actively engage within such dynamics and find the ‘alternative richness’ inside digital spaces.