Final Report By Daisy Sanchez Villavicencio

We have become familiar with the idea that large organizations like Universities are guided by Strategic Plans and produce annual reports. My research in the University of Toronto’s division of Student Life permitted me to examine the practices involved in this production and the rationality or mode of reasoning applied to making the abstract goals enunciated in the division’s Strategic Plan actionable, legible, and measurable. This report examines three modes of reasoning of particular importance. The first mode of reasoning concerned fungibility: the large scope of services offered and the complex needs of students should and could – with the correct tools – be firmly categorized to meet the criteria required by government and stakeholder economic policies. The second mode foregrounded a link between substance and form: carefully curated language and imagery could successfully reflect SL’s intrinsic values and morals. The third mode hinged on professional training: the skills required to write a strategic plan or conduct assessments of organizational changes could be attained through formal academic and professional training, and theories and works by acclaimed higher education scholars could serve as guides.

Research Approach

Adopting the inductive approach common in ethnographic research, I allowed my core questions to emerge from my immersion in the data. I particularly considered staff recollection of processes and events, their perception of the finished products (the Strategic Plan and Annual Report), as well as the epistemological underpinnings of their commitment to the organization and to defining and striving towards student success or wellbeing. From micro mannerisms, such as choice of words, to casual and formal references to literature and theories, a vast range of factors fascinated me. Additionally, all methods were conducted digitally in some form, which both inhibited my ability to consider more nuanced cues such as body language and allowed for a more detailed analysis of digital documents.

Participants

Three informants, all of them staff at Student Life, served as the participants of my ethnography. To maintain anonymity, I have labelled them Participant 1, Participant 2, and Participant 3.

Methods

- Participant observation

I attended a 4-hour course lecture taught by an interlocutor

- Interviews

I held structured and semi-structured interviews with three different staff members involved in the process of Annual Reporting or Strategic Planning

- Analysis of drafts, documents, and survey data

Documents provided by interlocutors, including drafts from the early planning process for the Strategic Plan as well as the hard data behind some of the Annual Reports and other assessments and course material (i.e., course readings and syllabi) were analyzed

Student Life and Organizational Change

Tucked away beneath the “About” section of the SL website resides the Mission statement, Strategic Plan, Annual Report, and Organizational Chart. Together, these four official documents meticulously outline the organization’s beliefs and commitments regarding their impact on undergraduate and graduate students’ experiences at U of T. They are the physical manifestation of Organizational Change, which I define as a form of knowledge that foments the teaching, discussion, and envisioning of structural change within higher education institutions. Departing from the conceptualization of organizational change as a mere happening or a natural sequence of events within organizations, Organizational Change at Student Life (as I understand it) refers to the politics of needing, desiring, envisioning, and enacting structural change at U of T. It comprises the work that staff do to clarify the organization’s purpose, identify student needs, devise appropriate strategies, and attend to accountability.

Purpose

The idea of purpose refers to how SL situates itself within the university. SL encompasses over ten different units, from Experiential Learning to Accessibility Services, all intended to enrich students’ experience and success by enhancing their quality of life beyond the classroom. In conversation with my interlocutors regarding the characteristics of this imagined quality of student life, I asked for a description of an ideal undergraduate student experience, followed by the interviewee’s perception of SL’s role in that experience. Participant 2 described an analogy of two axes, one representing challenges encountered at the university and the other the support received. Upward progression should be aligned so that challenges that are bound to occur at the university are always met with the appropriate support.

Student need

Though student needs were interpreted within the context of the purpose of the organization (to support student challenges experienced within the institution), I found there to be a sort of invisible man, or in this case an invisible student, who acted as a model to embody the two-axis analogy described by Participant 2. This invisible student steadily progressed through a four-year undergraduate program, asked for help when they needed it, received the appropriate support, attained their degree, and attained employable skills through co-curricular experiences.

Strategy

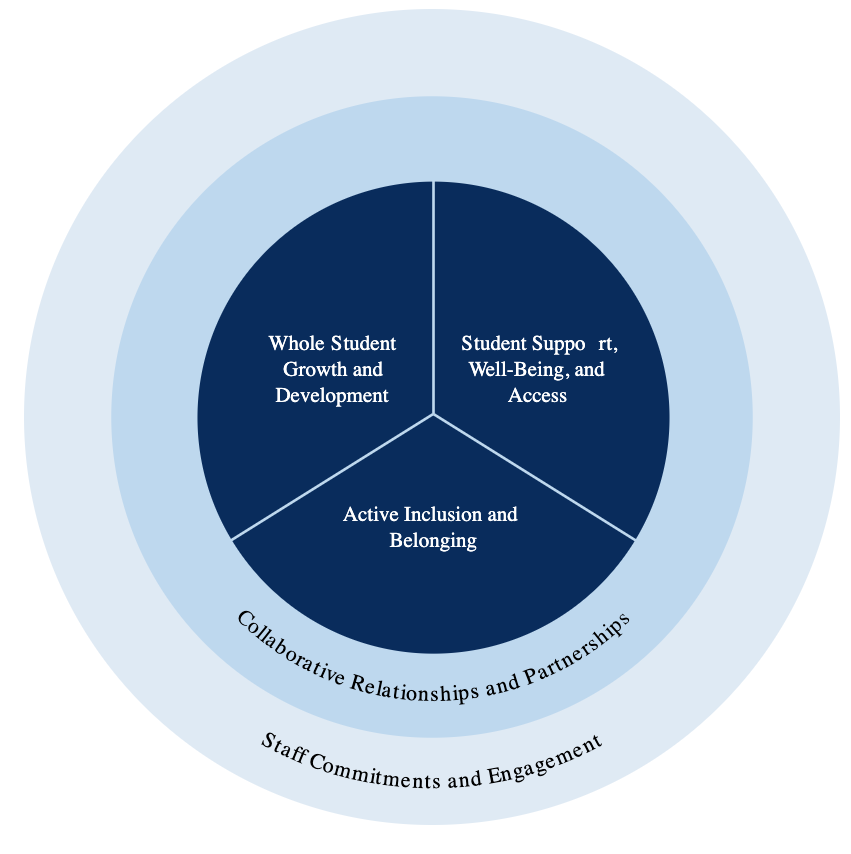

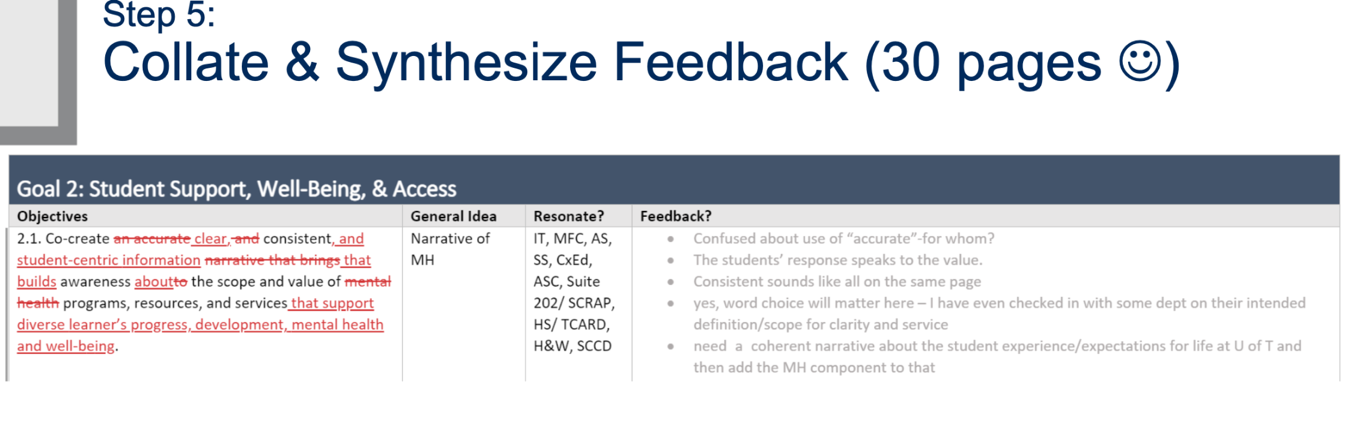

After clicking the “About “section, then “Strategic Plan & Annual Report,” we are brought to a separate website which entails much of the work my interlocutors conduct in the service of Organizational Change. The Strategic Plan is guided by five goals: “1. Whole Student Growth and Development, 2. Student Support, Well-being, and Access, 3. Active Inclusion and Belonging, 4. Collaborative Relationships and Partnerships,” and “5. Staff Commitments and Engagement” (See Figure 1). Under the “Annual Report & Operating Plan” subsection of this site, we find a detailed breakdown of each of the five goals of the Strategic Plan, with several sub points for how each goal will be manifested and the impact they can have. For example, for “1. Whole Student Growth and Development”, website users are guided to SL’s objectives for the goal, which take the form of 5 subpoints in this case. One subpoint reads; “1.1 Support a holistic student experience that values students’ lived experiences and draws on Indigenous approaches of learning and knowing, where appropriate.”, and is later associated with an Indigenous Educational event from 2023 on the latest Annual Report. Throughout the Annual Report, users see different articles entailing specific SL events and their associated goal and/or objective (subpoint). The strategy, in short, is to transform the challenges experienced by students into met needs and – through this process to reshape – higher education without engaging in radical structural reforms.

Accountability

The Annual Reports synthesize substantial amounts of data, collected via various feedback and assessment strategies to measure the impact of SL and efficiently report it to SL stakeholders. All three participants described SL as being most accountable to and influenced by their biggest funder: the student body (represented by various Student Unions, the Council of Student Services (COSS), and other student governing councils. Participants also expressed gaps between the ideals stated in the Strategic Plan (notably the professed devotion to the student body) and the conditions for their implementation. For example, Participant 2 recalls needing the goals to be as general as possible to encompass the diversity of the units that SL represents. When asked about the purpose of the Annual Report, specifically the Signature Program Assessments (SPA) published on the site in 2023, Participant 2 differentiated SPAs from hard data reporting and described them as a form of storytelling. Like a fairytale, these stories entail a challenge, a journey, and a destination. Accountability, in this case, refers to the ability to take something complex like data, feedback, or diverse needs and render it legible via storytelling.

The four defining aspects of Organizational Change at SL identified above can be understood as attempts to navigate the contradictory landscape of higher education as a third space where logics, such as neoliberal ideology and market imperatives on the one hand, and collegiality and academic freedom on the other, are in a constant tension.

What Rationalities Render Abstract Goals Operational?

The Strategic Plan is prepared by SL staff who operate from a third space, where they are neither students nor faculty. Their task is to render abstract goals operational and to offer solutions to problems that may be unsolvable. The fascinating transformation from abstract and unsolvable to operational, I argue, is informed by three main rationalities, briefly put as: fungibility, imagery and diction, and professionalization.

“Government Buckets” and Selling SL

SL, from its services to its staff members’ salaries, is funded by the imposition of compulsory, non-tuition related fees paid by enrolled undergraduate and graduate students. Student Life and its impact are simultaneously shaped by budgetary guidelines imposed by government policies and year-to-year expectations brought forward by student councils. As a result, my interlocutors often described the use of the Strategic Plan and the Annual Report in relation to justifying budgetary increases in order to better meet student needs. Government funding policies also shape and constrain SL’s impact. In 1994, the Government of Ontario introduced the Compulsory Ancillary Fee Policy Guidelines (CAFPG), which determined the management of non-tuition related fees in higher education. According to the guideline, students must be involved in any decisions related to the increase of ancillary fees. Consequently, COSS was formed in 1996 and has facilitated the involvement of students in budgetary changes. Each year, SL staff formulate an Annual Report and Operating Plan, which is presented to COS,S and budget increases are subsequently proposed and approved or disapproved by student representatives. The CAFPG policy and the formation of COSS have contributed to a broader ethos of accountability, legibility, and, more recently, efficiency within SL visions for change. To receive appropriate funding and continue to enact change at the university, my interlocutors described a sense of pressure to justify SL services by explaining how they link to specific goals. Hence the Annual Report brought life to commitments enunciated in the Strategic Plan, such as “2.2 Provide proactive and timely supports that focus on students’ social determinants of health (e.g., finance, health, housing), and are culturally responsive” by associating it with a particular initiative, such as “Peer Support Service Pop Ups.” In this way, the Annual Reports act as a form of ritual for transforming something complex into something coherent, and ultimately something useless into something urgent.

Another impactful policy that was cited by all three of my participants was a 2019 policy enforced by the Government of Ontario and Premier Doug Ford, titled The Student Choice Initiative (SCI), which granted post-secondary students the liberty to opt out of non-essential ancillary fees such as those issued by student unions. Though the initiative was heavily contested by students leading to its repeal in December 2019, my interlocutors vividly recount the effects of policies like SCI on SL. Participant 2 recounted that the SCI imposed an essential versus nonessential binary for the services offered by SL. Though academic, health, and wellness-related services were broadly deemed essential, many services such as sexual, race, or gender identity-based support groups and bike rental services, which they describe as extensions of the various determinants of student wellbeing, were excluded. This binary of essential vs non-essential echoes the concept of biopower, as described by Michel Foucault, which brings our attention to the role of structures of power in determining whether something is essential, and ultimately whose rights are protected and whose aren’t and overall, whose lives are valued and who’s aren’t (Li, 2022).

On the matter, Participant 1 described an analogy for the impact of the policy on their work, stating, “There were some protective buckets that government had identified around health, accessibility, and other things like that. Our job was to try and figure out how we could categorize several programs and services to fit into those mandatory buckets.”. I found myself fascinated with the concept of a bucket, a firm container with a purpose of being filled and transporting things that many archaeologists and anthropologists have cited as a monumental human invention, used to represent the rigidness imposed by power logics foregrounding governmental policies such as the SCI and certain accountability requirements. For Participant 1, the act of compartmentalizing services at SL into their respective buckets meant that the Strategic Plan and Annual Report team were pressured to employ several tactics, such as storytelling and innovative assessment strategies (described in further depth later), to assure that certain services conformed to guidelines for essential services. For example, in response to the exclusion of identity-based support groups, the act of synthesizing data that measures student’s experiences of community, acceptance, and belonging (or lack thereof) at the university and its effects on mental health and performance can transform an aspect of a student’s life into a crisis in need of intervention. I argue that the rationalities employed to maintain many of various SL services were centered around creating a form of deficiency; that experiences of isolation amongst students are a mental health related crisis rather than an institutional one, or that by investing in certain services there will be a tangible measurable payoff, as if the protection of human rights has profitable results. In this sense, students have become subjects of a consumer economy and blatant consumers themselves, and Student Life, and the services it offers, a commodity.

Language and Imagery

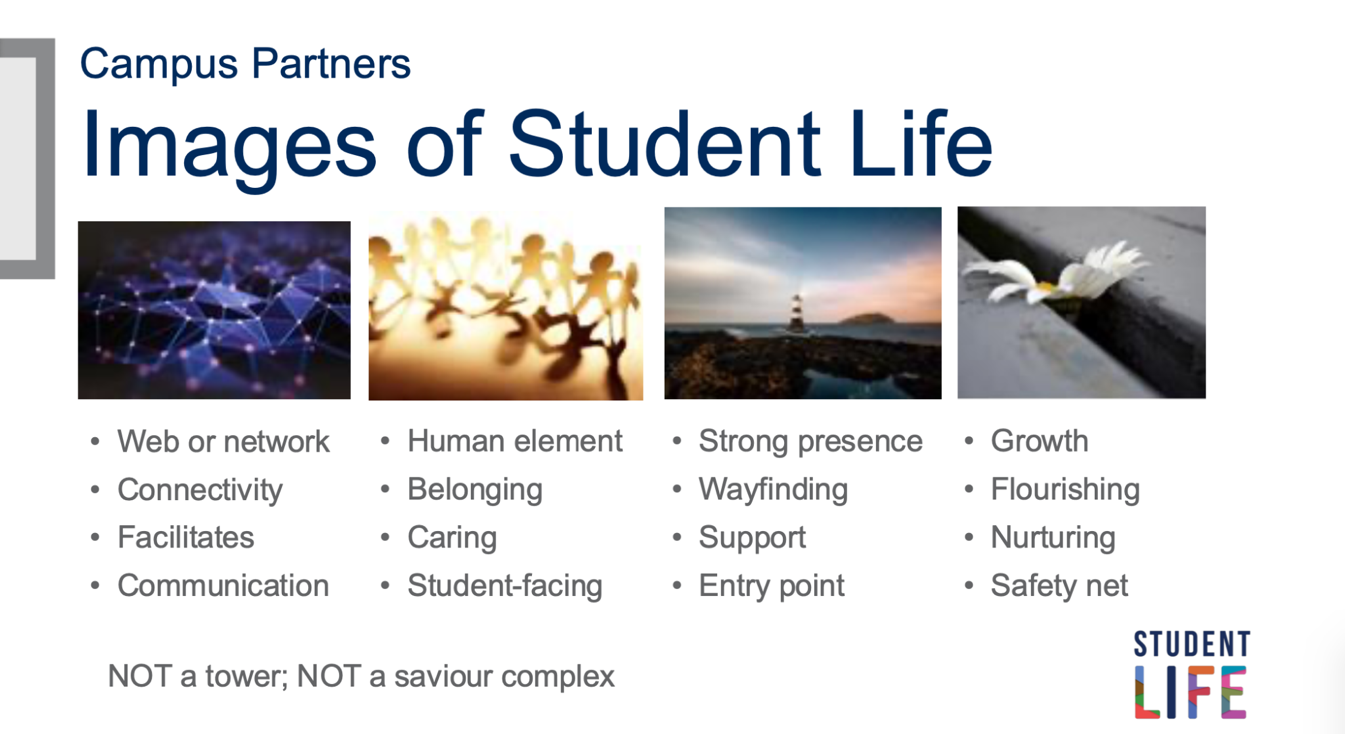

Historically, higher education has been regarded as a public good rooted in values such as academic freedom, autonomy, and democracy. However, with rising global competition, the prominence of university rankings, and an influx of post-secondary students, institutions like SL have begun to resemble corporate enterprises, adopting branding and marketing tactics to legitimize their services and attract stakeholders. According to my interlocutors, this dynamic creates significant pressure to “sell” SL’s services—not in the literal sense but in terms of justifying their value and securing support, particularly from students, COSS members, and other funding bodies. The mission statement, though concise, carries immense weight, tasked with distilling the collective values of over 350 staff members into a few sentences. This challenge rests on two assumptions: first, that carefully worded and formatted language can embody a unified vision for a diverse organization; and second, that SL’s ethics and practices emerge from a stable, tangible core rather than being continuously reiterated or performed. Each unit within SL also contributes to this vision by crafting its own mission statements, often through workshops like those led by Participant 1, which help align individual units’ goals with SL’s overarching ethos. Beyond the mission statement, SL relies heavily on storytelling in documents like the Annual Report to render its complex and abstract goals accessible to stakeholders. Participant 2 described this process as an alternative to presenting hard data, favoring narratives that highlight the efficacy of SL’s services through relatable challenges, journeys, and outcomes. This storytelling approach allows SL to appear flexible and inclusive, reflecting a wide range of experiences while sidestepping the rigidity of statistical reporting. By simplifying complexity, SL can present itself as coherent and actionable, resonating with students, staff, and stakeholders alike. At its core, the “selling” of SL’s services is a performance of legitimacy, achieved through the deliberate curation of language, imagery, and visual elements. Participant 1 recalled how this process often involved sifting through extensive feedback, with debates over terms like “equity deserving” exemplifying the contested nature of language in institutional contexts. As advised by the University Equity Director, SL ultimately embraced a pragmatic approach, selecting terms that balanced inclusivity with functionality and committing to revise them over time. Similarly, imagery in documents like the Annual Report and Strategic Plan serves a dual purpose: signaling SL’s identity while differentiating it from undesirable associations, such as a savior complex (as illustrated in Figure 1.1) or an overly corporate image (see Figure 1.2). Together, these facets of the branding process (crafted mission statements, coherent storytelling, and curated visual elements) demonstrate how staff utilize writing processes to balance varying organizational values with the need to appeal to a market. Ultimately, these efforts mirror a staged ritual or ceremony, where SL’s values and practices are performed and rendered legible to an audience of students, consumers, and stakeholders, simultaneously promoting its vision and securing its legitimacy (Briody, 2018, p. 190).

Figure 1.1

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.3

Note. Student Life, 2021, University of Toronto.

Figure 1.4

Manning, 2012, p. 3

Professionalization

Strategic planning in higher education has increasingly been formalized into a distinct professional field where individuals are trained to lead organizational change. Within this space, SL experts, such as Participant 1, navigate complex tensions between the grand ideals of change and the practical realities of implementation, between academic freedom and corporate efficiency, and between their own personal experiences and the institutional structures they serve. Participant 1 is positioned at the nexus of conflicting fields of practice within the academy: they are a U of T alumni, an OISE course instructor, and a staff member of SL. Curious about how one becomes an expert in writing an operational plan, I was compelled to learn more about the masters cohort course at OISE they were teaching and hopefully find some theoretical underpinnings for my fieldwork. What I found instead was a sort of “regime of practices” where knowledge, power, and discourse intersect. Professionals in this field must acquire technical skills, like analyzing governance structures or critiquing policy. Foucault’s theory of discourse as a system of rules offers a useful lens to understand the professionalization of strategic planning, and its implications for the operationalization of abstract goals. According to the course syllabus and learning outcomes, organizational change and the field of higher education are not neutral but deeply tied to power knowledge. What counts as valid knowledge, what constitutes a “good” strategic plan, and who qualifies as an expert is understood according to a criterion for expertise. As this course teaches students to analyze higher education structures, apply theoretical concepts, develop actionable change initiatives, and critically assess strategic plans, it also corrects and molds students into experts. Additionally, an integral aspect of being an expert in this field was to embody the perceived skills and values associated with a successful higher education professional. I observed this on two separate sites; in the OISE course material, such as the syllabus and lecture slides, the authoritative figure required students to be able to perform critical assessments of organizational change and use relevant examples of experiences in life or the workplace to show an understanding of the course material. The second occasion occurred during a semi structured interview with both Participant 1 and 2, where both described their interest in attaining post-undergrad education in higher education organization related fields and the mission and values behind SL as an almost natural sequence of events emerging from a “calling” from childhood experiences or more recent life events. In this case, the expertise is embodied by professionals by being understood as a trait that they were either born with or that they naturally developed in response to a life circumstance, such as having school-aged children or having been an active student in their own elementary experiences.

Organizational change within higher education, as exemplified by Student Life at the University of Toronto, is not an organic or reflexive process but one profoundly shaped by socialization within institutional and societal frameworks. Just as mundane acts of courtesy are cultivated through layers of correcti

on, modeling, and instilled values, the practices of universities are meticulously constructed through processes of learning, negotiation, and justification. My ethnographic study revealed three key rationalities—categorization, the strategic use of language and imagery, and professionalization—that underpin the transformation of abstract goals into operational and measurable frameworks. These rationalities enable Student Life to navigate the pressures of accountability to students and external stakeholders while maintaining its legitimacy and purpose. By categorizing diverse services to align with funding policies, crafting narratives and visuals to convey coherence and inclusivity, and cultivating expertise through professional training, Student Life exemplifies how higher education institutions render the illegible legible. Further, social institutions, such as higher education corporations, colleges, and universities, both engage with and continuously actively construct values and practices, creating a symbolic identity and various subjectivities, from student subjects to professional employee subjects.

References

Briody, E. K., Berger, E. J., Wirtz, E., Ramos, A., Guruprasad, G., & Morrison, E. F. (2018). Ritual as Work Strategy: A Window into Organizational Culture. Human Organization, 77(3), 189–201.

Ian Austin, Glen A. Jones, Coates, H., Hazelkorn, E., & McCormick, A. C. (2018). Emerging trends in higher education governance: reflecting on performance, accountability and transparency. In Research Handbook on Quality, Performance and Accountability in Higher Education (pp. 536–547). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Li, T. M. (2023). Foucault foments fieldwork at the university. In Philosophy on Fieldwork: Case Studies in Anthropological Analysis, Edited By Nils Bubandt and Thomas Schwarz Wentzer (pp. 214-230). Routledge. Manning, K. (2012). Organizational Theory in Higher Education. Taylor & Francis Group.